Aza

Пользователи-

Постов

1821 -

Зарегистрирован

-

Победитель дней

3

Тип контента

Информация

Профили

Форумы

Галерея

Весь контент Aza

-

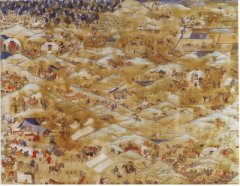

Worthy stateswoman Sorkhugtani Bekhi, the honourable bride of the Chinggis Khaan There are many wonderful, brave and women in Mongolian history. Alun Goo, Uulun Ujin, Burte Tsetsen, Tsever khatan (Chabi), Mandukhai Tsetsen, Anu were the queens, who sustained Mongolian Great Empire, poet Agai, E.Oyun, Udwal were famous ladies, who greatly contributed Mongolian State. One of those well known ladies, Mandukhai the Wise, was not only brave and prudent, but also prominent military commander, leader. Comparing to Joan de Ark, she was much better than Joan. I would like to introduce one of the most trustworthy brides, wise queen, famous stateswoman Sorkhugtani Bekhi. From “Wretched King Arag Buke” book… Sorkhugtani Bekhi met with Tului prince at young age. When the Chinggis Khaan was in close relationship with Wan Khaan Tooril, he made engagement between his son Tului, and Sorkhugtani, a daughter of Jahar Khambu, who was a brother of Tooril’s. Later, in 1203, after the elimination of Khereid tribe, Sorkhugtani and Tului were married. Sorkhugtani was the most beloved queen of Tului, also trustworthy bride of Chinggis’s. “Altantovch” by Luvsandanzan, Mongolian great King Chinggis and his son Tului felt exhaust together. Fortuneteller said, one of them must be recovered and another one should be fallen. So that, Chaur Bekhi, Tului’s queen, prayed to Heaven “If King Chinggis shall fall, the empire shall suffer, if my husband falls, only I shall suffer. Heal the great king, Heaven!” . Soon, the king got better and pleased with her. Since that, the queen had been given an honorary title “Bekhi Taikhu”, and 8 Tsakhar clans to her control. Later, her husband, Tului saved his brother Ugudei king with his life, too. Also she had been written in many historical books like Uulun queen. In 1231, Tului had gone to his noble ancestors at the age of 38. It was hard to grew up children alone was difficult duty for Sorkhugtani queen. Once, Ugudei king sent emissary to bring Sorkhugtani queen on the purpose of marrying her once more. Even she accepted, she had been entitled to grow up her children. Uulun Ujin married to Menlig, Sorkhugtani didn’t, so she was more honest her husband. Even though Sorkhugtani Bekhi queen had no trouble like Uulun Ujin’s, she looked after her children very well. The four sons of Tului, Sorkhugtani Bekhi were Munkh, the 4th great king of Mongolian empire, Khubilai, founder of Yuan dynasty, king Khulegu, founder of Il Khaan dynasty in Far-East, and Arag Buke, the 5th great king of Mongolian Empire. The four sons played in important roles on the world’s history; it says how Sorkhugtani Bekhi was wise mother. Chinggis, the Great, divided his empire into four sections to his four sons. Zuchi’s descendants, the eldest son of Chinggis, inherited the vast land from Erchis river to Black Sea, Tsagaidai, the second son received Western and Eastern Turkmenstan, Ugudei, inherited the throne, also the land from the basin of Emil river to Jungar, Tului, the youngest son accepted whole Mongolia due to ancient tradition. But, Tului’s descendants were much poorer, weaker than other Chinggis’s sons’ because of Ugdei’s assignment. So Sorkhugtani Bekhi queen grew up her children very well and her chidren all became noblemen and kings thatnks to her mighty efforts. It seems, she palyed an important role like Uulun Ujin. In “Sutra Session” or “Sudryn Chuulgan”, “… after the death of Tului, his wife and chilren left under the care of Ugudei king. Once, Sorkhugtani Bekhi queen wanted to get a merchant of king’s. But, the king didn’t agree it. Thus, Sorkhugtani Bekhi queen complied and cried “For whom, my husband sacrificed himself? Who needed his death!”. The complaining reached the king’s ears soon, and finally, he gave her some merchants. At that time, her children were youngsters. Again, Uguudei gave 2000 households to Godan, which were under the control of Sorkhugtani’s. Some representatives of those civilians came to see the queen and her eldest son, Munkh. They said that they were given to Sorkhugtani Bekhi queen by the order of Chinggis Khaan. But now, Godan got us. Should we go to great king’s faint judge? Sorkhugtani Bekhi replies “You are right. However, my family has no honour and glory. Also, we don’t need soldirs and civilians anyhow. Great king knows what he must do. We should obey his order.” The noblemen pleased with her words…” Academic Vladimirtsov wrote about her “… Sorkhugtani Bekhi was a wise woman. Thanks to her wise, generous and humble characters, she educated her children as the kings.” In “Mongolian history”, by Plano Carpini, “…Sorkhugtani Bekhi queen is the second most important queen among Tatars. Only the mother of Guyg king, Naimalj queen is superior to her.” In fact, she was. Lord Chormogan was sent by the order of Ugudei king in order to govern conquered Far-east countries. In additon, all provinces governors were sent one emissary due to king’s decree. Therefore, according to the King’s decree, Khorasan, Chintumur from Masander, came for Chormogan. Other emissaries came from prince’s countries including: - Kol- Bulat from Ugudei’s - A lord from Bat’s - Kizil from Tsagadai’s - An emissary from Sorkhugtani Bekhi’s Each representative came from each Khan huvguud (striplings) in order to establish relay station, and they went through the whole country. After the measurement of the land, they set destination of the relay station. The following people established the station firstly: Khuridai, a representative of The great King Uguudei, Imkhalchin and Taichutai – Tsagaadai Suku and Mulchitai- Bat, and Iljigdei noyon by the issue of Sorhugtany Behi khatan (queen) – Tului Khan. It is confirmed not only the agreement and cooperation in ownership states of the Chinggis Khaan’s four children, but also how Tului’s reputation was higher when Sorhugtany khatan was permitted in decision making even Tului was dead and his children were not reached the age of consent. It seemed, Sorhugtany Behi participated in any political affairs actively like this way during the difficult periods after her husband’s death. After the Great session, intended for Guyug to be a Khaan, Sorhugtany Behi and her children were greatly praised for their wonderful example. Therefore, Guyug Khaan would consult with Sohrugtany Behi more than his mother, Naimaalz, if he needed to make some important decisions. In the late of winter, 1248, Guyug Khaan set off a journey by covering of the following matter to confound Bat, argued with Guyug during the period of war in Western Europe and made Guyug left the battlefield. “The weather is getting to be warmer. The climate in Emil is really suited me. The water and climate will be affected in my illness.” said Guyug. When Guyug went to the west, Sorgutany Khatan sent an envoy to Bat in order to make known about it and to be carefully. Guyug could not confound Bat, and then he passed away in Ilyn Khundy. After his funeral rites, as an oldest son of Chinggis Khaan’s family, Bat Khaan, sent envoys in all directions and invited other Kans and lords in order to discuss about a new Khaan by convening The Great Session. Posterities of Uguudei and Tsagaadai didn’t agree with it, so saying “Chinggis Khaan’s motherland and permanent abode are on the Basin of Kherlen River. So, why will we go to the Bat’s Hivchaagyn area? ”. Then they sent a few representatives, including Tumur, a chief of Khar-Korin capital city and lords, non – considered the Golden family. However, Sorhugtany Behi confirmed to Munkh that he would come with his brothers and grant an audience to their sick brother due to Khaan huvguud don’t care their older brother’s command. In addition, she sent a letter that is “Bat is the oldest brother of the other Khans and his every words and decree are a law to be followed by us. That’s why, we have to agree with his idea and follow his decision.“ It was noted that “The meeting of Alagtag “, because the Great session was held in the region of the Alagtag lake at this time. At the meeting, a preliminary resolution to install Munkh on Mongolian fourth throne was made and they decided to install him as a real Khaan by re-convening The Great Session on the Basin of Kherlen River, next spring. As soon as a sensation to install Munkh as a Khaan spread in all directions, Sorhugtany Behi started to present a lot of gifts and donations to attract public and The Golden family’s attention. As a result of efforts made by posterities of Juchi, especially Sorhugtany Behyn such riskable acts, Munkh became a Khaan during the time when there was a throne transition between posterities of Ugudui and Tului.33 of Mongolian 35 Khaans from the Golden family are Tului’s Posterities. Efforts and intelligence of Sorhugtany Behi khatan were really efficient and important in above –mentioned historical circumstances. It is said that Sorhugtany Behi khatan was Christianity. Although Khar-korin, the capital city in given period, covered a smaller territory, it was the main political heart of the world. Even though there were some high developed countries such as Buhar, Samarkhand, Baghdad, Constantinople, Cordova and Han joy of Eastern China, none of them were such influential and powerful. Various nationalities such as Saracen soldiers with scowling look and white thin silk gauze covering, catholic jossers, Russian Catholics, Arthurian merchants and others used to come in Khar-korin. The religious sector was free. There were Buddhist, Christian, Nestorian and Muslim had their own monasteries and churches. From the note of Rubric, there were not only a district of merchants, sartuul and Med Asian Muslim’s, and a district of craftsmen dominated by Chinese, but also a lot of big palaces of lords and dignitaries. There were also 12 temples for various worships, 2 Muslim churches and a Christian church. All of these religions tried to convert the citizens, maintained in Central Asia, suddenly. It would provide at least their securities. However, Mongolians used to have all of these religions without any depression or differences. This is one of the evidence that Mongolian Empire was great. Historians explain that it was influenced for foreign occupations. Mongolians are tolerant and patient in any foreign religions. Various nationalities and different ethnic groups have their own ideas about Buddha. Comparing, even though a sharp mountain is different such as rough, dirty, straight and etc, the top is only one. Like this, Buddha is only one concept that includes saving road, study of truth, purification of humanity’s mind. Mongolian lords and dignitaries used to know about such truth. There is one example that testifies such thing: When Munkh Khaan called Rubrik, an envoy of Ludoviq. XI, France. to come his palace. Then Munkh Khaan said,“Mongolians believe that there is only one Buddha. However, Buddha taught different ways like it gave different fingers to every person. Even tough Buddha gave you sutras (Buddhist book), you don’t follow it. And Buddha gave doctors and diviner for us, however, we live by restricting these rules in the world.” This means that Munkh Khaan was not Buddhist, he was a shamanist. Sorhugtany Behi Khatan, intelligent and clever, did not believe not only Christian, but also she prayed for Hai –Yun, a famous religious protector, and Tsoi- Junhga. Unfortunately, religious representatives wrote and left if a Mongolian person is positive for any religion, that person is written – religious. On the behind, there were political secret interest and activities. In 1242, when Mongolians have attacked to Europe twice, a younger brother of Munkh Khaan captured French craftsman Wilhelm Bush from the City Belgrade, Major. Sorhugtany Behi Khatan required to Munkh Khaan several times to give that craftsman for her, because his ability of ironsmith was incredible. Then she made him her citizen. After the Khatan’s death, her all properties and craftsman Wilhelm Bush belonged to Arigbukh. Wilhelm Bush crafted a famous silver tree flowing honey, mare’s fermented milk, wine etc… by the signal of an Angel with a trumpet in front of the Khaan’s palace in Khar-Korum. Even tough he was a captured man, he lived satisfied, trouble-free and abundance. . It is not only related with Wilhelm Bush, but also other foreigners. Temuge Behi, only one daughter of Tului, studied about Buddhism, especially Hai-yun’s religious teachings. However, Hulug Khaan, a Christian benefactor and a historical person made Buddhist monastery, forbidden in Muslim world, build. Khubilai Khaan distributed to develop Buddhism and he proclaimed that this religion is the state main religion. . If we look such activities of Tului’s Posterity, we can know that they were respecting knowledge and perfect. Sorhugtany’s influence was really efficient. The death of outstanding people is surprising. Sorhugtany Behi’s death was not normal. In 1251, as soon as Munkh became a Mongolian 4th Khaa, he killed some people of Golden Family in order to put down the protest of Ugudei and Tsagaadai’s posterities to Haimish Khatan, who didn’t agree with the decision. At that time, Munkh Khaan executed about 75 people of the Golden family. Sorhugtany Behi’used to say for her son: “You should conduct merciful policies, because you are just newly elected Khaan. Also, you should solve gradually the issue about Haimish Khatan and her sons’ due to it is a relational problem.” Unfortunately, Munkh Khaan did not treat his mother’s sayings and started to execute his relatives hardly. That’s why, Sorhugtany Behi’ didn’t like it and she became hollow from the politics by going to northern part in Khar-Korin with her youngest son Arigbukh. She lived in the area among Jarantai, and Tsagaan Sumyn River, by herding cattles. She grows old quickly because of bad feeling and sense. Next year, she was dead in the Summer Palace of Arigbukh Khaan. During the time when she had a normal life, she granted a lot of donations for vulnerable poor people who come to pray in Khar-Korin. According to “Session of Sutras”, her remain was buried in Buddha /the land name / Undur, The Chinggis Khaan’s Great protected area. Except Khubilai Khaan, all other Khan huvguud were buried there. As a result, Sorhugtany Behi khatan was buried like a Khaan. Even tough Sorhugtany Behi used to restrict and require Chinggis Khaan’s sayings for her sons; she loved public and religious praying. Only one example that shows her kindness and mercy, and she used to act charitable activities, is she gave 1000 gold to build a school in Bahrain. About 1000 Muslim children enrolled to. The school. Islam and prayers called the school “The school of the Khatan (queen)” by dedicating her honor. This building is still now. Nowadays, if you are in Bahrain or interested to go to Bahrain, you should search about this topic. Then you will be surprised. Today, a document related to sorhugtany Behi Khatan attracting this document is a book “ Melody of State golden truth to develop Sky Mongolia” read by heart by herself. According to order of Chinggis Khan, Tsagaadai, Esui, Chutsai, Doloodoi and Sorhugtary Behi Khatan wrote three volumes, defined Chinjuu policy of Mongolian State. Sorhugtany Behi who influenced on the creation of state. Great Sutra has been studied with other scientists and novelists. However, after the death of Ugudei, in 1245, his wife sent this 3 volumes book to Turkina Arac. In 1251, when Munkh became a king there was no any heritages which could show Mongolian traditional black-box policy, and wisdom of reign. Thus, Sorhugtany khatan /collected/chosen the best plats of such 3 volume-book to make it “ Altan ayalguu”. When Munkh became a king, she read it by her heart for him. It’s an interesting history that this 3 volume book, published in 1251, has been saved for 750 years. Thus work/ masterpiece published in 1251 had been saved for 750. Between 1958 and 1962 Nurzed Jurnai, a academics of nomadic civilization and an engager learned by heart and inherited the book “Golden Melody”from his cousin Legjin older Maaramba lama and a subject of Sahil soum, Uvs aimag, thus. Sky Nohoi(dor) tribes had inherited the book for their 15 generations. It was their merit for culture history of their nationality. Nurzed translated the book “Golden Melody” into presents Mongolia, published and showed to scientists and researchers. According to meaning concept of “Golden Melody”, it defined Mongolian history, state policy, life, language and culture of 12th century. However, it is necessary to study the book anymore. When we see this book, we can see that there are not only wisdom words and proverbs been also some lyrics which showed existence of the state and people in the world. That an idea which Sorhugtang Bahikhatan was perfect minded / intelligent when she was creating such book. For example: “ Even though a lian is born to eat ostrich and antelope, it can’t satiate when it eats only rabbits. Even though a wolf and a leopard are born to eat wild goat and wild mountain sheep. It’s unnecessary to eat follow-chat for them. Even though the state has a duty to encourage its citizens, it’s not a good thing to be supported by Tunbao etc…

-

Доктор Ислам и вы тоже наверное "не заметили" этот факт.Там на белом по чёрному написано,что керейты и найманы говорили на монгольском. Это на язык кереев, найманов, коныратов, меркитов и жалаиров оказал влияние кипчакский язык. Однока вас ув.Хаджи Мурат назвал "аматеур хисторианам".

-

Вы раньше говорили,что ногайские ашамай найманы это керейлер.А сейчас говорите другое.

-

АКБ вам остается доказать,что язык ТИМ это тюркский.Потому что, ТИМ написано на керейтском.

-

Имена монгольских ханов. А мынгүл это тысяча цветок.Верно?

-

-

Это трудновато.Я знаю только одного подрода Айгар.Это маньчжуры у нас займствовали этот слово.Об этом доказал уже американец .С вами что? Проблема с английским? До этого маньчжуры были тоже оленоводами как керейты, жалайры.Я считаю,что Жалайры есть настоящие тунгусы. К стати,я всегда считал ,что Бек это тюркизм.Но оказывается это китайзм.Паик инь.

-

-

А я сомневаюсь.

-

Ну все же ясно.Он тоже поленился и как вы.Все надо рассматривать по научному, учитывать малейших "не заметных факторов".

-

Нет Уважаемый. По моему маньчжуро-эвенкийский язык это забытый керейтский язык.И днк эвенков тоже потверждает это. Я вам посоветовал почитать труд америнканского маньчжурведа Уйльям Розицки.И тоже я вам напоминал о народе Мекритов\Керейтов\-оленоводов.Вы поленились.Причина гибели Ванхана может обьясниться в том, что керейты имели оленные солдаты и воевали против коннои армии Чингисхана? А вы там видели доказательства ,что керейты ездили на олене?.

-

Монгольский Хотон-мусульманин с женой.

-

А если он владеет маньчжурским и эвенкским? Тогда думаю переводчиков не нужны.

-

Н. А. Баскаков К ПРОБЛЕМЕ КИТАЙСКИХ ЗАИМСТВОВАНИЙ В ТЮРКСКИХ ЯЗЫКАХ (Turcica et Orientalia. Studies in honour of Gunnar Jarring on his eightieth birthday. - Istanbul, 1987) Еще сто лет тому назад известный русский синолог академик В.П. Васильев обратил внимание на необходимость изучения взаимодействия китайского языка с языками Средней Азии (Васильев, 1872). Однако эта проблема пока еще слабо разработана. Некоторые достижения в этом отношении имеются в области исследования китайских лексических элементов только в уйгурском языке, что объясняется необходимостью их изучения в связи с непосредственным соседством и тесными контактами китайцев с уйгурами, живущими главным образом в пределах Китайской Народной республики - в Синцзяне и частично в Казахской, Киргизской и Узбекской ССР. Наряду с этимологическими ссылками в различного рода словарях на заимствования отдельных слов из китайского языка (Радлов, 1911, Юдахин, 1938; Баскаков, Насилов, 1939; Jarring, 1964; Наджиб, 1968 и др.), были опубликованы также и специальные монографии о китайских элементах в уйгурском языке (Новгородский, 1951; Рахимов, 1970), в которых приведен уже значительный материал и осуществлена большая исследовательская работа по истории этих заимствований, но главным образом в области общественно-политической терминологии и современной бытовой лексики без привлечения старых китаизмов в основном словарном составе других тюркских языков. Интересные сведения о взаимодействии и взаимовлиянии китайского и уйгурского языков, кроме словарей и указанных выше специальных исследований можно встретить в общих работах по уйгурскому языку и его диалектам (Малова, 1928, 1954, 1956, 1957, 1961, 1967; Катанова-Менгеса, 1933; Raquette, 1927; Насилова, 1940; Тенишева, 1976; Кайдарова, 1969; Садвакасова, 1970, 1976), а также в трудах по итсории, этнографии народов Синьцзяна и по другим тюркским языкам других авторов так или иначе касающихся данной проблемы (Валиханов, 1904; Пантусов, 1898; Катанов 1906; Deguignes, 1756-1758; Köprülü, 1938; Eberhardt 1941; Pritzak, 1952; Ecsedy, 1965, 1968; Menges, 1968; Gabain, 1973). В меньшей степени изучен вопрос о китайских заимствованиях в древне-тюркских языках, специальные исследования по китайским элементах в которых до сих пор отсутствуют, хотя и существуют некоторые древнетюркские словари (ДТС, 1969; Ligeti, 1966; Clausin, 1972; Gabain, 1974) а также общие исследования по истории древних тюрок и по древнетюркским языкам, в которых отмечаются китаизмы, но также без привлечения тех же китайских заимствований в основном словарном составе других тюркских языков (Радлов, 1897, 1899; Малов, 1951, 1952; Бернштам, 1940, 1946; Jarring, 1936 и др.). Наименее разработанным вопросом этой проблемы остается вопрос о китайских заимствованиях в лексике основного словарного состава т.е. в общетюркской лексике современных тюркских языков, в то время как китаизмы могут быть, и в значительном количестве, вскрыты в составе лексики каждого современного конкретного языка. Ранее уже отмечалась необходимость изучения тюркско-китайского лексического взаимовлияния на более ранних ступенях развития тюркских языков, в эпоху более тесного контактирования тюркских и китайского народов (Баскаков, 1951, 1962), но количество конкретных примеров заимствования ограничивалось тремя, четырьмя словами. Вместе с тем при более внимательном изучении китаизмов в тюркских языках обнаруживается уже более значительное их количество. Учитывая все предыдущие исследования и привлекая вновь устанавливаемые китаизмы, мы приведем ниже анализ свыше сорока китайских слов, относящихся к общетюркской заимствованной лексике, т.е. встречающихся в большинстве тюркских языков и главным образом в западных языках исключая новоуйгурский и некоторые восточные тюркские языки - алтайский, хакасский, тувинский, якутский, в которых кроме общетюркских китаизмов встречаются также и заимствования, характерные только для данных языков, народы-носители которых в истории своего формирования имели более тесные связи с тюркскими народами близкими соседями с Китаем. Если рассматривать китаизмы в тюркских языках по тематическим группам, то наиболее многочисленные слова относятся: К первой группе - названиям титулов и различных должностей и профессий: baqšy ~ baqsy 'сказитель'; bek ~ beg 'бек, господин'; čur ~ čora ~ šora 'сын хана'; jabγu ~ žabγu 'титул верховного правителя'; qaγan 'государь'; qam 'шаман', syrčy 'маляр, художник'; tajšy 'сын знатного человека'; tarxan 'звание, освобожденного от налогов'; tegin 'принц'; Tojun ~ tudun ~ turun 'титул провинциального правителя'; tutuŋ ~ tutuq 'губернатор, генерал'; xan 'хан'; župan 'титул чиновника'. Вторую группу составляют китаизмы, обозначающие предметы и понятия духовной культуры: а также отвлеченные понятия: bitik ~ bičik 'книга'; burqan ~ burxan 'Будда'; čyn ~ čin 'истина, истинный'; küg ~ küj 'песня, мелодия'; lu ~ luŋ 'дракон'; tuγ ~ tu 'знамя, флаг', zaŋ 'закон, обычай'. Третью группу составляют китаизмы - слова обозначающие различные вещества и металлы: altyn ~ altun 'золото'; čaj 'чай'; čini 'фарфор'; čojun 'чугун'; indžü ~ indži 'жемчуг'; suγ ~ suw 'вода'. Четвертую группу - китаизмы-слова, обозначающие предметы быта и прочие имена: čan 'сосуд, стакан'; čanaq 'посуда'; džaj 'место, дом'; iš ~ is 'дело, работа'; ütük ~ ötük 'утюг'; paj 'доля, пай'; qap 'мешок'; taŋ 'утро, восход солнца, заря'. Пятую группу - китаизмы-слова, обозначающие имена прилагательные и глаголы: čoŋ 'большой'; quw 'сухой'; tyŋ 'сильный, очень'; tyŋla- 'слушать'; biti- 'писать'. Все перечисленные выше слова-китаизмы встречаются не только в уйгурском языке и отчасти в тюркских языках Сибири, но и во всех остальных тюркских языках Средней Азии и Восточной Европы. Хронологически китаизмы, заимствованные в тюркских языках, принадлежат как к довольно раннему, так и к позднему времени, но некоторые из них, органически вошедшие в основной словарный состав относятся невидимому к весьма древней эпохе, например слова: čoŋ 'большой', džaj 'место, дом', iš ~ is 'дело, работа', qap 'мешок', quw 'сухой', suγ ~ suw 'вода', taŋ 'утро, заря', teŋ 'ровный', tyŋla- 'слушать', которые в современных языках уже не осознаются как заимствования. В лексико-семантической структуре тюркских языков китаизмы являются как правило изолированными омонимами по отношению к другим словам, не связанными словообразовательными парадигмами и этимологически трудно объяснимыми внутренними средствами тюркских языков, и таким образом заимствование их из китайского языка представляется весьма вероятным. Считая вполне естественной и верной теорию о происхождении аффиксов словообразования и словоизменения в тюркских языках, имеющих агглютинативный строй, т.е. строй, обуславливающий сочетание самостоятельных слов, из которых постпозиционные слова в процессе морфологического развития грамматикализовались и превратились в служебно-грамматические элементы, можно допустить наличие и таких аффиксов, которые исторически также представляли собой заимствованные самостоятельные слова из китайского языка. Примерами последних могут служить например аффикс -džy ~ -či ~ -šy /с вариантами/, образующий словообразовательные модели в тюркских языках со значением профессии, ср. например: temir 'железо', temir-či 'кузнец', в котором аффикс -čy/-či происходит либо из кит. чжи-е /1/ [1] 'профессия', либо из кит. žen' /2/ 'мужчина, человек, лицо, персона' (Чень Чан-Хао, 1953, 655, 899; Рамстедт, 1957, 209) или аффикс -čaŋ ~ -šaŋ /ср. казахск. söz-šeŋ 'словоохотливый/ < кит. čjan /3/ 'мастер' (Рамстедт, 1957, 210; Чэнь Чан-Хао, 1953, 326). Ниже мы приведем китайско-тюркские параллели, иллюстрирующие китайские заимствования в тюркских языках, как установленные ранее тюркологами, так и предлагаемые к обсуждению автором данной статьи. 1. тюркск. altyn ~ altun 'золото' <тюркск. ala ~ āl 'красный' + кит. tun /4/ 'медь > красная медь > золото' (Чэнь Чан-Хао, 1953, 328); āl 'красный' + кит. ton /4/ 'медь' > altun 'золото' (Räsänen, 1969, 18, 488). 2. тюрк. baqšy ~ baqsy 'сказитель' < кит. ро-shi ~ pâk-ś ~ pâk-dzi /5/ 'мастер, учитель' (Gabain, 1974, 326; Ramstedt, 1951, 73). 3. тюрк. bek ~ beg 'бек, господин' < кит. paik /6/ 'белый, благородный' встречается в сочетании paik in /6/ > begin 'губернатор провинции' (Ramstedt, 1951, 67). 4. тюрк. bičik ~ bitik 'книга' < кит. pi < piet /7/ 'кисточка для письма' > тюрк. biti- ~ piti- ~ biči- 'писать' + -k аффикс, образующий результат действия > bitik ~ bičik 'книга' (Новгородский, 1951, 45; Gabain, 1974, 329). 5. тюрк. biti- ~ biči- 'писать' < кит. pi ~ bi < piet /7/ 'кисточка для письма' > biti- ~ biči- 'писать' (Новгородский, 1951, 45; Gabain, 1974, 329). 6. тюрк. burxan ~ burqan 'Будда' < кит. fo /8/ + xan' /47/ > fo-xan' /9/ > burxan (Gabain, 1974, 332). 7. тюрк. čaj 'чай' < кит. ch'a /10/ 'чай' (Колоколов, 1935, 598; Чэнь Чан-Хао, 1953, 896; Räsänen, 1969, 95). 8. тюрк. čan 'сосуд, бокал, стакан' < кит. chan /11/ 'стакан' (Gabain, 1974, 333; Räsänen, 1969, 98). 9. тюрк. čanaq 'посуда' < кит. chin /12/ 'китайский' + ajaq 'чашка' > čanaq 'посуда' (Räsänen, 1969, 111). 10. тюрк. čini 'фарфор' < кит. chin /12/ 'Китай, китайский' (Räsänen, 1969, 111). 11. тюрк. čojun 'чугун' < кит. t'siu ~ choj + kâng /13/ 'металлический сосуд > чугун' (Räsänen, 1969, 113; Ср. Фасмер, IV, 374). 12. тюрк. čoŋ 'большой' < кит. čaŋ /14/ 'длина, длинный' (Räsänen, 1969, 116). 13. тюрк. čora ~ šora 'сын хана' < кит. čol ~ čor > čora ~ šora /15/ (Ramstedt, 1951,77). 14. тюрк, čyn ~ čin 'истина, истинный' < кит. chên /16/ 'верный' (Gabain, 1914, 334); < кит. чжэнь /17/ 'истинный, верный' (Новгородский, 1951, 46-47); < кит. чын /18/ 'истинный, верный, честный' (Колоколов, 1935, 511); < кит. t'śan (Räsänen, 1969, 108); ср. кит. чжэнь-ли /19/ 'истина' (Чэнь Чан-Хао, 1953, 248). 15. тюрк. džaj ~ žaj 'место, дом', предполагаемое заимствование из персидского džaj < кит. džaj) /20/ 'дом, жилище, квартира' (Колоколов, 1935, 539; Чэнь Чан-Хао, 1953, 264). 16. тюрк. indži ~ indžü 'жемчуг' < кит. džen-džu /21/ 'жемчуг' (Чэнь Чан-Хао, 1953, 179; Räsänen, 1969, 203). 17. тюрк. iš ~ is 'дело, работа' < кит. shi ~ šhih /22/ 'дело, занятие' (Колоколов, 1935, 294; Чэнь Чан-Хао, 1953, 137). 18. тюркск. jabγu ~ žabγu 'правитель, вождь', предполагаемое заимствование из иранск. кушанск. санскритск. jawγu (Golden, 1980) < кит. djan-giwo > современ. šan-ju /23/ 'титул верховного правителя' (Menges, 1968, 88; Gabain, 1974, 381). 19. тюркск. küg ~ küj 'песня, мелодия' < кит. kü < k'iok /24/ 'песня' (Gabain, 1974, 343). 20. тюркск. lu ~ luŋ 'змея, дракон' < кит. lung /25/ 'дракон' (Чэнь Чан-Хао, 1953, 157; Räsänen, 1%9, 318). 21. тюркск. paj 'доля, пай' < кит. p'aj /26/ 'ряд' (Räsänen, 1969, 378). 22. тюркск. qaγan 'каган, государь' < кит. Ke-xan' /27/ 'великий хан' (Чэнь Чан-Хао, 1953); < кит. ke-kuan /28/ 'великий государь' > qaγan (Ramstedt, 1951, 62). 23. тюрк. qam 'шаман' < кит. kam /29/ 'шаман' (Ramstedt, 1951, 71). 24. тюрк. qap 'мешок' < кит. kia > kap /30/ 'карман' (Gabain, 1974, 355). 25. тюрк. quw 'сухой' < кит. ku ~ qiu /31/ 'засохнуть' (Колоколов, 1935, 109). 26. тюрк. suγ ~ suw 'вода' < кит. shuj ~ shuej /32/ 'вода' (Колоколов, 1935, 410; Чэнь Чан-Хоу, 1953, 68). 27. тюрк. sürčy sirčy 'маляр, художник' < кит. ts'i ~ ts'iet /33/ 'лак, лакировщик, художник' (Gabain, 1974, 365); < кит. tsi /34/ > sir 'лак' (Чэнь Чан-Хао, 1953, 305; Räsänen, 1969, 418). 28. тюрк. tajšy 'принц' < кит. t'aj-tšeng /35/ 'принц' (Räsänen, 1969, 456). 29. тюрк. taŋ 'утро, восход солнца, заря' < кит. tan ~ dan' /36/ 'утро, восход солнца' (Колоколов, 1935, 16). 30. тюрк. tarxan 'звание, освобождающее носителя от налогов' < кит. t'ât /37/ 'благородный, знаток' (Ramstedt, 1951, 63). 31. тюрк. tegin 'принц' < кит. tek in /38/ 'знатный человек' (Ramstedt, 1951). 32. тюрк. teŋ 'ровный, равный' < кит. t'an ~ tan' /39/ 'равнина, широкая ровная поверхность' (Колоколов, 1935, 16). 33. тюрк. teŋri 'бог' < кит. čen-li /40/ 'бог' (Benzing, 1954, 685). Ср. Pelliot,1944, 185. 34. тюрк. tojun ~ tudun ~ turun 'титул правителя, ученый, мудрец' < кит. tao-jĕn < d'âo-dö-ńźiĕn /41/ 'ученый, монах, мудрец' (Gabain, 1974, 373); < кит. tao-jên 'князь, учитель' (Räsänen, 1%9, 484; Чэнь Чан-Хао, 1953); < кит. tao-in /41/ 'князь, учитель, епископ' (Ramstedt, 1951, 70). 35. тюрк. tuγ ~ tuw 'знамя, флаг' < кит. tu < d'uok /42/ 'знамя, флаг' (Gabain, 1974, 374). 36. тюрк. tutuŋ ~ tutuq 'губернатор' < кит. tutu ~ tu-tuok /43/ 'губернатор' (Räsänen, 1969, 502); < кит. to-thoŋ /44/ 'правитель области' (Ramstedt, 1951, 70). 37. тюрк. tyŋ 'сильный, сильно, очень' < кит. taŋ /45/ 'сильный, сильно' (Räsänen, 1969, 478). 38. тюрк. tyŋla- 'слушать' < кит. tiŋ /46/ 'слушать' (Чэнь Чан-Хао, 1953, 750; Räsänen, 1969, 478). 39. тюрк. ütük ~ ötük 'утюг' < кит. juĕt-təng > wej-dou /47/ 'утюг' (Boodberg, 1939, 263). 40. тюрк. xan 'хан' < кит. хань /27/ 'хан' (Чэнь Чан-Хао, 1953, 879); < кит. kuan /48/ 'хан' (Ramstedt,1951, 61). 41. тюрк. zajsaŋ 'родовой старшина' < монг. dzajsaŋ 'чиновник, судья' < кит. tsâj-siang /49/ (Ramstedt, 1951, 76). 42. тюрк. zaŋ 'закон, обычай' < кит. jaŋ /50/ 'модель, образец' > монг. zang 'закон, обычай' (Räsänen, 1969, 186) < кит. дъянь ~ дьянь /51/ 'модель, образец' (Колоколов, 1935, 573). 43. тюрк. župan 'титул провинциального чиновника' < кит. tsou-pan /52/ 'секретарь, канцлер' (Ramstedt, 1951, 72). 44. тюрк. temir 'железо' < кит. te-pi /53/ 'железные куски, листы' (Чэнь Чан-Хао, 1953, 169). 45. тюрк. kümüš ~ kümiš, чувашск. kĕmĕl 'серебро' < китайск. корейск. kim 'металл, золото' < кит. *kiəm-liən /54/ 'серебро' (Ramstedt, 1949, 116; Joki, 1952, 103; Räsänen, 1969, 308). 46. тюрк. syn ~ sin 'намогильный камень' < кит. ts'in 'камень-памятник' (Räsänen, 1969, 422). 47. тюрк. tabčan 'диван' < кит. tao-ch'iang /56/ 'диван, софа' (Räsänen, 1969, 452). Большинство из приведенных выше китаизмов в тюркских языках уже было выявлено ранее различными исследователями, из предложенных же нами китайских этимологии тюркских слов džaj ~ žaj 'место', iš ~ is 'дело', quw 'сухой', suγ ~ suw 'вода', taŋ 'утро', teŋ 'ровный', наиболее вероятными являются: džaj ~ žaj 'место, дом', quw 'сухой', teŋ 'ровный' и taŋ 'заря, утро', которые не только совпадают в отношении семантики и звукового состава с соответствующими китайскими словами, но и в большинстве тюркских языков являются омонимами по отношению слов с другими значениями, а кроме того, за исключением слова taŋ 'заря' не являются также общетюркскими словами и не встречаются как правило в огузских языках и в некоторых других группах тюркских языков. Менее вероятны сближения с китайской лексикой являются слова iš ~ is 'дело, работа' и suγ ~ suw 'вода', которые, однако, также имеют с соответствующими китайскими словами общую семантику и фонетическую структуру, хотя и являются общетюркскими словами, общими для большинства тюркских языков. В задачу настоящей статьи входит главным образом необходимость обратить внимание тюркологов на данную проблему с тем чтобы последующие исследования в этой области были более подробно разработаны не только для современного уйгурского языка, специальные монографии по которому уже представлены в тюркологии (Новгородский, 1951 и Рахимов, 1970), но и для каждого современного тюркского языка. Примечания 1. Цифры в скобках указывают на номер иероглифа в таблице, приложенной к настоящей статье, каллиграфически выполненной аспирантом Института Языкознания АН СССР Ясином Ашури. Литература Баскаков, Н.А., Очерк грамматики ойротского языка. В кн. Н.А. Баскаков и - Т.М.Тощакова, Ойротско-русский словарь, Москва 1947. - Предисловие к кн. В.И. Новгородский, Китайские элементы в уйгурском языке, Москва 1951. - Состав лексики каракалпакского языка. В кн. Исследования по сравнительной грамматике тюркских языков, т. IV. Лексика, Москва 1962. Баскаков, Н.А. и Насилов, В.М., Уйгурско-русский словарь, Москва 1939. Бернштам, А., Уйгурские юридические документы. В кн. "Проблемы источниковедения", Сб. 3, Ленинград 1940. - Социально-экономический строй орхоно-енисейских тюрков, VI - VIII вв., Москва - Ленинград 1946. Валиханов, Ч.Ч., Сочинения. Записки Имп. Русск. Геогр. Об-ва по Отделению Этнографии, т. XXIX, С. Петербург, 1904. Васильев, В. П., Об отношении китайского языка к средне-азиатским. Журнал Мин. Народн. Просвещ., IX, 1872. Древнетюркский словарь /сокращенно ДТС/, Ленинград 1969. Кайдаров, А.Т. , Развитие современного уйгурского литературного языка, Алма-Ата, 1969. Катанов, Н., Маньчжурско-китайский "Ли" на наречии тюрков Китайского Туркестана. Записки Вост. Отд. Русск. Археолог. Об-ва. т. XIV, С. Пегербург, 1902. Колоколов, В.С., Краткий китайско-русский словарь. Москва 1935. Малов, С.Е., Характеристика жителей Восточного Туркестана. Доклады Ак. Наук СССР, Ленинград 1928. - Уйгурский язык. /Хамийское наречие/. Москва - Ленинград 1954. - Лобнорский язык. Фрунзе, 1956. - Язык желтых уйгуров. Алма-Ата, 1957. - Уйгурские наречия Синьцзяна, Москва - Ленинград 1961. - Язык желтых уйгуров /Тексты и переводы/. Москва 1967. - Памятники Древнетюркской письменности. Москва - Ленинград 1951. - Енисейская письменность тюрков /Тексты и переводы/. Москва - Ленинград 1952. - Памятники древнетюркской письменности Монголии и Киргизии. Москва - Ленинград 1959. Наджиб, Э.Н., Уйгурско-русский словарь, Москва 1968. Насилов, В.М., Грамматика уйгурского языка. Москва 1940. - см. Баскаков Н.А. и Насилов В.М. Новгородский, В. И., Китайские элементы в уйгурском языке. Москва 1951. Палтусов, Н.Н., Материалы к изучению наречия таранчей Илийского Округа, I, С. Петербург, 1890; II, Казань, 1898; III, Казань, 1901. Радлов, В. В., Опыт словаря тюркских наречий, I - IV, С. Петербург, 1893-1911. - Образцы народной литературы северных тюркских наречий, VI, С. Петербург, 1886. Рамстедт, Г.И., Введение в алтайское языкознание, Москва 1957. Рахимов, Т. Р., Китайские элементы в современном уйгурском языке. Москва, 1970. Садвакасов, Г.С., Язык уйгуров Ферганской долины, Алма-Ата, I, 1976, II, 1970. Тенишев, Э.Р., Строй саларского языка, Москва 1976. - Строй сары-югурского языка, Москва 1976. Фасмер, М., Этимологический словавь русского языка, I - IV, Москва 1964-1973. Чэнь Чан-Хао, А.Г. Дубровский, А. В. Котов. Русско-китайский словарь, Москва 1953. /Сокращенно - Чэнь Чан-Хао/. Юдахин, К. К., Уйгурско-русский словарь, ред. Москва, 1938. Benzing, J., Das Hunnische, Donaubolgarische und Wolgabolgarische. Filologiae Turcicae Fundamenta, I, Wiesbaden, 1959. Boodberg, P.A., Ting-ling and Turks. Sino-Altaica, II (5), Berkeley, 1934 - Marginalia to the Histories of the Northern Dynasties. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Cambridge, Mass. IV, 1939. Clauson, G., An etymological dictionary of pre-thirteenth century Turkish, Oxford, 1972. Deguignes, J., Histoire générale des Huns, des Turcs, des Mongols et des autres Tartares occidentaux, ouvrage tiré des livres chinois, Paris, 1756-1758. Eberhardt, W., Die Kultur der alten zentral- und westasiatischen Völker nach chinesischen Quellen, Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, 73, 1941. Ecsedy, H., Old Turkic titles of Chinese origin, Acta Orientalia Hungarica, 18, Budapest, 1965. - Trade- and war relations between the Turks and China, Acta Orientalia Hungarica, 21, Budapest, 1968. Gabain, A. von, Das Leben in uigurischen Königreich von Qočo. Wiesbaden 1973. - Alttürkische Grammatik. 3. Aufl. Wiesbaden, 1974. Golden, B.P., Khazar Studies, I-II, Budapest, 1980. Jarring, G., The contest of the fruits. An Eastern Turki allegory. Lund, 1936. - Materials to the Knowledge of Eastern Turki, I-III, Lund, 1946-1951. - An Eastern Turki-English Dialect Dictionary, Lund, 1964. Joki, A.J., Die Lehnwörter des Sajansamojedischen. Memoires de la Société finno-ougrienne, 103, Helsinki, 1952. Köprülü, M.F., Zur Kenntnis der alttürkischen Titulatur. Körösi Csoma Archivum (1938), Budapest - Leipzig, 1938. Ligeti, L., Sur quelques transcriptions sino-ouigoures des Ynan. Ural-Altaische Jahrbücher, XXXIII, 1961. - Un vocabulaire sino-ouigour des Ming. Acta Orientalia Hungarica, Budapest, 1966. Menges, K.H., Volkskundliche Texte aus Ost-Turkistan aus dem Nachlass von N. Katanov. Sitzungsbericht. Berl. Akad. Wiss., 1933. - The Turkic languages and peoples. Wiesbaden, 1968. Pelliot, P., Tangrim > tarim, T'oung-Pao, 1944. Pritzak, O., Stammesnamen und Titulaturen der altaischen Völker. Ural-Altaische Jahrbücher, 24, Wiesbaden, 1952. Radloff, W., Die alttürkischen Inschriften der Mongolei. St. Petersburg, 1897. - Alttürkische Studien, I-VI. St. Petersburg, 1909-1912. - Uigurische Sprachdenkmäler. Leningrad, 1928. Ramstedt, D.J., Alte türkische und mongolische Titel. Journal de la Société Finno-Ougrienne. Helsinki, 1951, Vol. 55. - Studies in Korean Etymology. Memoires de la Société Finno-Ougrienne, XCV, Helsinki, 1949. Raquette, G.R., English-Turki Dictionary. Leipzig, 1927. Räsänen, M., Versuch einen etymologischen Wörterbuchs der Turksprachen, Helsinki, 1969.

-

"Tanzeem Nasle Nau Hazara Moghul (TNNHM)" means 'Organization of Hazara Mughul's New Generation'. Its based in Quetta where thousands of Hazaras live. "Tanzeem Nasle Nau Hazara Mughal was founded with this vision that all human beings are equal and equality comes through the national entity which takes its roots through process of history with in the orbit of cultural identity. If we conceive it through epistemology, diversified civil society is the outcome of cultural identity that safeguard and protect the fate and future of a people. We have to focus our vision to the challenges facing our people’s identical issue over the years. Efforts should be made through collective means to put an end to ethnic and religious conflicts and confrontation that broke out under the framework of confronting ideologies that took place during the past era. We also feel it out right to have desire for; a society in which the dignity of individuals and the diversity of culture and civilization are respected is now being sought. Today the world has entered into the 21st century and in order to establish such a society in which multi-cultural and multi societal issues are to be resolved through mutual relationship between nationalism, regionalism and globalism and the image of the world, it is essential to struggle for the security of our people from various perspective, including politics, economy, society and culture. Tanzeem Nasle Nau Hazara Mughal is a national organization and basically stem its existence from the notion that ‘You are’, ‘I am’ and ‘I am you are’ and the desire to live with dignity can’t but to be accomplished through national interaction. To get to this aims and objective of Tanzeem Nasle Nau Hazara Mughal which was engineered by the founding members is rooted to the pragmatic approach for the Hazara people and to the integration in the world community. We desire to strengthen amongst our people the awareness and commitment to human dignity, tolerance, justice, honesty, fair play, positive and constructive approach to life. We desire to live in a world with the elimination of terrorism, extremism, religious, intolerance, obscenity and discrimination of any account, and to harness the full potential of our people for advancement of the nation, community, family and individuals. And finally we desire to strive towards the creation of a just and human society, based on values and principles of respect for human rights, democracy, and equality of all citizens, regardless of their race, religious, class, caste, gender, ethnicity or language. This organisation runs a number of schools and hospitals for Hazara communites in Pakistan and Afghanistan. TNN Hazara Moghul's Chairman and Air Marshal Sherbet Chingizi. Today is a special day not just for Naimans, but also for all the other tribes. A young TNNHM member speaking.

-

Хотоны умножаются тоже как казахи.Большая часть хотонов сейчас в Сэлэнгинском аймаке, на земле меркитов .В чем секрет?

-

Среди монгольских жалайров есть род Айгар.Это по казахски ажирга?

-

Он же на фото у себя на береге Туула Кара Тунэ. Вы по английски пишите?